Is it safe to travel to Burma? Ethics and unrest in 2015

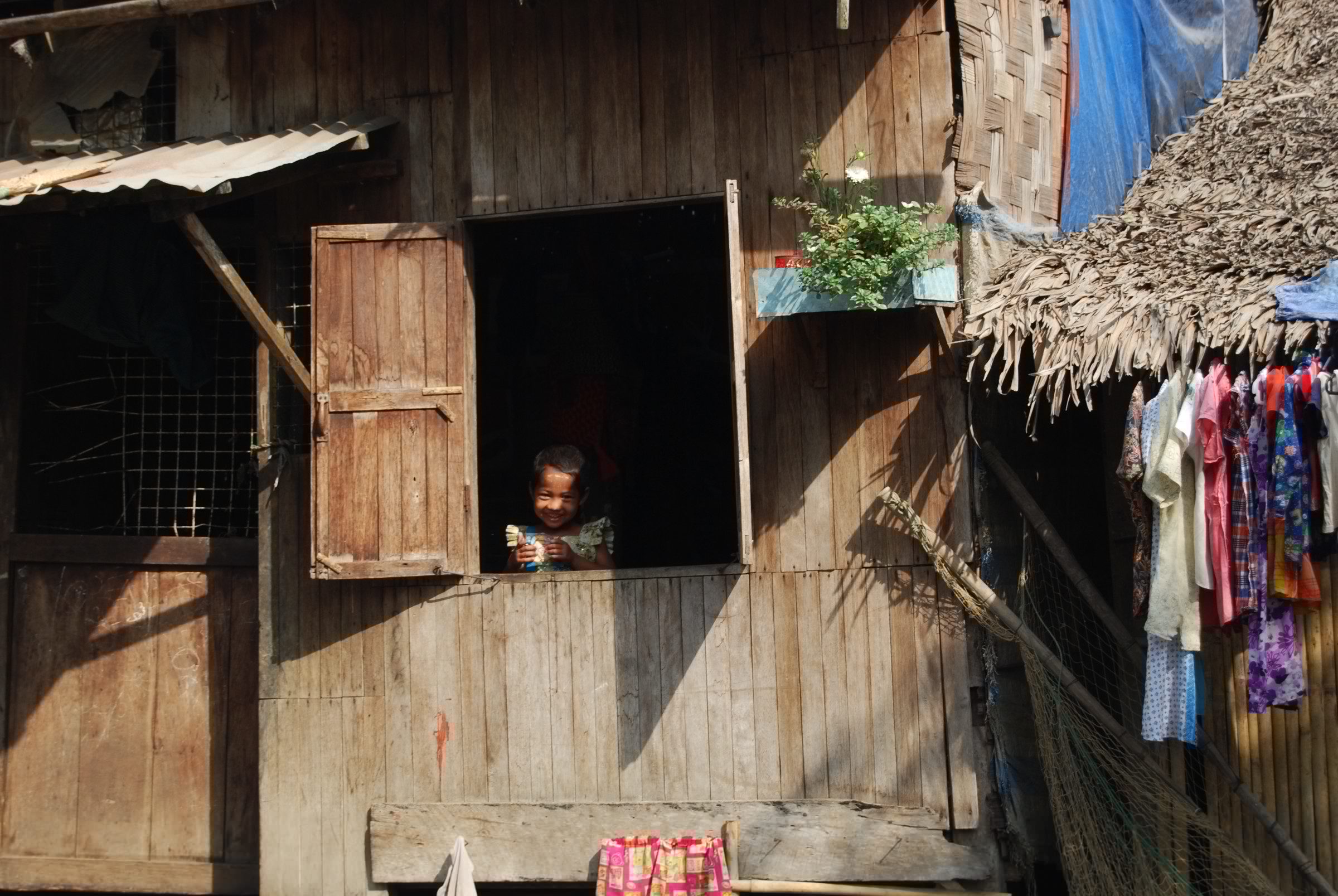

In recent months we have seen a fantastic rise in public interest in travelling to Burma, which is great news for the country and its people. However, we also occasionally hear from potential travellers who are put off by worries about personal safety in the country – or who doubt the ethical propriety of encouraging tourism to an area where corruption and human rights abuses are still rife.

If you’ve had half an eye on the regional news recently, you can hardly have missed the fact that all is not well in Burma.

Burma has long been in the grips of one of the world’s longest-running civil wars, which began in 1948 and continues in some areas to this day. While the country has made substantial steps in the right direction since 2010, (the military junta has taken a step back from government, political prisoners have been released, some repressive laws have been amended), Burma’s struggles are far from over.

Rather than shy away from these questions, we think it’s important to address them. As we discussed in a recent post, we believe that educated, responsible tourism to Burma now, and in the coming years, is going to be critical to the country’s development.

What is happening in Burma now?

Rakhine State

Much of the furore currently surrounding Burma in the news recently concerns the Rohingya people in northern Rakhine State – to the west of the country. The Rohingya are a Muslim people of ethnic Bengali origin, and though they themselves claim to have originated in Rakhine (also known as Arakan), the international consensus is that they migrated there from Bangladesh. This migration began very slowly as early as the 15th century, and increased after 1826 when the British annexed Arakan and encouraged farm workers to migrate to the area. Today the Rohingya number about 1.3 million and form about 40% of Rakhine State’s population. In northern Rakhine, however, Rohingya constitute about 80-98% of the population.

Violence between Rohingya and ethnic Rakhine people first broke out during World War II, following which the Rohingya were suppressed over the course of two decades by the Burmese leader Ne Win – who eventually removed their voting rights in 1982. Instead of being considered citizens, for the past three decades most of the Burmese Rohingya population have been categorised simply as “stateless Bengali Muslims from Bangladesh”, without rights in a country where they were born and raised.

The troubles of the Rohingya first came into the international spotlight in 2012, when the Rohingya majority in northern Rakhine clashed with the ethnic Rakhine majority in the south, leaving around 200 dead and tens of thousands displaced from their homes. CNN estimates that there are still more than 100,000 Rohingya trapped in internment camps, where conditions are squalid and the residents are forbidden to leave - "for their own safety".

Earlier this month, a bill was passed by the Burmese government that would allow “white card” holders (which includes most Rohingya) the right to vote in a referendum on the country’s constitution – a temporary measure that would not grant citizenship to Rohingya but which would give them a voice in the country’s affairs. The day after the announcement, however, thousands of Buddhist protesters took to the streets of Yangon demanding that these newly conferred rights be revoked. That same evening, President Thein Sein gave into pressure, announcing that the white cards would now expire at the end of March, and the Rohingya's newfound voting rights with them.

Following the expiry of the white cards, any Rohingya who can prove that their ancestors settled in Burma before 1823 will be granted citizenship, while all others will be turned away (according to Human Rights Watch).

Kachin State

Besides the recent troubles in Rakhine State, Burma has also seen a recent surge in conflict in Kachin State in the north of the country. The conflict began when Burma gained independence from Britain in 1948, and the Kachin Independence Organisation was formed in 1961. Since the mid-1960s the state has functioned virtually independently (except for its major towns and railway corridor), with its own extralegal police, fire brigade, education system, immigration department and other institutions.

Fighting resumed between the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and the Burmese Army in 2011, after a 17-year ceasefire, when government forces attacked KIA positions along the Taping River. Fighting spread throughout the state, continuing sporadically through 2012 and early 2013. In November 2014 there was one reported attack – by the government on a KIA headquarters. During the conflict, both the Burmese Army and rebel forces are said to have acted without regard for civilian lives – even targeting them on occasion.

Shan State

Next-door to troubled Kachin State, Shan State has also recently given cause for concern. Shan State is home to numerous ethnic groups - some of them with their own armies. Though most of these groups signed a ceasefire with Burma's military government, in mid-February this year fighting broke out between ethnic Chinese rebels in the Kokang district of northern Shan and the Burmese Army, leading to the imposition of martial law in the Kokang Self-Administered Zone by the Burmese government. Many civilians have fled the area, seeking refuge in neighbouring China.

Fighting has now died down in the area, and some people are returning to their homes - although many continue to stay away. Unusually, the Burmese government is actually reported to have won much support over their handling of the incident - even from former political prisoners of the regime - by allowing media updates on the situation and inviting reporters to sit in on briefings.

The vast majority of Shan State has been unaffected by the recent skirmish, and remains safe to travel.

Will I be safe?

If you avoid problem areas, keep an eye on local news, and follow sensible travel advice – yes, your visit will most likely be trouble-free. The risk to your safety in most parts of Burma is very low – lower, in fact, than in many other popular tourist destinations in the developing world – and we are very happy to continue sending customers to Burma, and indeed to continue visiting Burma ourselves, in 2015.

As of 20th February 2015, the UK government advises against all but essential travel to Rakhine State and Kachin State (marked in orange on the map below), except to the beach resort of Ngapali (in Rakhine) and the towns of Myitkyina, Bhamo and Putao (in Kachin). These areas are considered safe and continue to accept large numbers of tourists.

Particular care is also advised when visiting border areas with Thailand, Laos and China, where there have occasionally been armed clashes in the past few months. Further protest rallies (such as the recent, violently dispersed student protests in Yangon) are expected regarding recent legislation, so if you come across protests or demonstrations while in any part of Burma, you are also advised to stay well clear of the crowd and refrain from taking photographs or videos – especially of police.

![FCO 303 - Bangladesh Travel Advice [WEB]](/sites/default/files/blog/2015/02/burma-map.jpg)

Is it ethically responsible to travel to Burma now?

While personal safety is not a major issue for foreign tourists to Burma, a more troubling subject for many prospective travellers is whether their visit is ethical. Historically, forced labour is known to have been used in the preparation of tourist sites and infrastructure in Burma, and it is impossible to know whether the money you spend will end up supporting the local community or lining the pocket of some corrupt official.

Are you you – and we – approving the Burmese government’s continuing human rights abuses by feeding them our tourist cash?

Burma’s opposition leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, has asked tourists to stay away from Burma in the past. In 1999, she said:

"I still think that people should not come to Burma because the bulk of the money from tourism goes straight into the pockets of the generals. And not only that, it's a form of moral support for them because it makes the military authorities think that the international community is not opposed to the human rights violations which they are committing all the time. They seem to look on the influx of tourists as proof that their actions are accepted by the world."

Aung San Suu Kyi (Photo: asiasociety.org)

This call for a boycott was honoured by many (including the UK and other EU countries) until 2011, when the National League for Democracy (NLD), Aung San Suu Kyi’s party, announced that it would now welcome responsible tourism to Burma. The party made the following statement:

"The NLD would welcome visitors who are keen to promote the welfare of the common people and the conservation of the environment and to acquire an insight into the cultural, political and social life of the country while enjoying a happy and fulfilling holiday in Burma."

So what changed? The decision by the NLD to make an about-turn on tourism may have been influenced by a number of factors.

For a start, the actual effectiveness of a boycott on travel that was only really respected by a handful of nations is small. Though the Western world may have stayed away for the most past, Asian investors (mainly from China and India) did not – meaning that the boycott held relatively little sway over domestic developments.

Meanwhile, although Aung San Suu Kyi has suggested that international tourism could be seen as a stamp of approval for the Burmese regime, it could also be argued that the more international onlookers there are in the country, the less keen the Burmese government will be to carry on with their abuses of human rights. Similarly, the more tourists visit Burma to learn about its political situation and get to know its people first-hand, the more exposure these problems will get – and the more pressure the Burmese government will be under to effect real change.

Though different opinions do exist on the matter and it remains a subject under debate, we believe that responsible, thoughtful tourism to Burma is integral to the country at this critical stage in its history. The question at hand is not whether human rights abuses are continuing to happen in Burma (we know that they are), but whether by withholding tourism we are really having a positive effect on the situation.